Why do we collect things?

Desire, nostalgia, loss, and completeness in the personal collections of Joseph Cornell, Peter Blake, and Vladimir Nabokov

“Every passion borders on the chaotic, but the collector’s passion borders on the chaos

of memories.”

–Walter Benjamin, Unpacking My Library

This is an essay about the things we keep.

One of my earliest memories is of walking home from school — I must have been in the third or fourth grade? — and finding a giant garbage bag of my toys, knick-knacks, my things on the curb in front of our townhouse.

When I confronted my mother about it inside, she explained that she’d cleaned out the house, including my room. “But it’s my stuff,” I said. “Piojito, you get too attached, it’s just stuff, you don’t even use it.”

Note: “Piojito” means “little louse” in Spanish. It was (and still is) her nickname for me, and yes, it’s related in part to my being “too attached” to things.

Things I’ve collected over the years:

(1) Handwritten notes and cards; (2) gifts from loved ones (which yielded a favorite subcategory of handmade coin purses, dolls, fans, rosaries, and other souvenirs from my grandparents’ travels); (3) ribbons, string, and gift-wrapping paper and bows; (4) flowers, which were pressed or dried; (5) rocks, after my first-ever best friend showed me his fancy rock collection; (6) shells, always and forever; (7) random small creatures (tadpoles, lizards, minnows) and not-yet-hatched eggs found in my childhood neighborhood, which my mother put a stop to real quick

But this essay is not about my collecting tendencies or my sentimental attachment to things — not specifically anyway.

In her ethnographic study of material possessions in New York City, researcher and designer Sam Bennett asked, “The things we keep silently, but visually tell a story of us. Is this why we keep them?”

This essay is an attempt to answer that question by weaving together some of the loose threads on the subject that for years have been floating in my brain and in my bookmarks, Notes, and notebook pages.

As old as man

“Noah was the first collector,” write John Elsner and Roger Cardinal in their introduction to The Cultures of Collecting.

“Adam had given names to the animals, but it fell to Noah to collect them: ‘And of every living thing of all flesh, two of every sort shalt thou bring into the ark, to keep them alive with thee…’ (Genesis 6.19-20). Menaced by a Flood, one has to act swiftly. Anything overlooked will be lost forever: between including and excluding there can be no half-measures. The collection is the unique bastion against the deluge of time. And Noah, perhaps alone of all collectors, achieved the complete set, or so at least the Bible would have us believe.”

Bible aside, we know that collecting goes at least as far back as 105,000 years ago, with people in the Kalahari region of Southern Africa collecting crystals, likely for spiritual reasons. Later on, ancient civilizations in Egypt, Babylonia, China, and India collected objects as symbols of wealth and status to place in their temples, tombs, and sanctuaries.

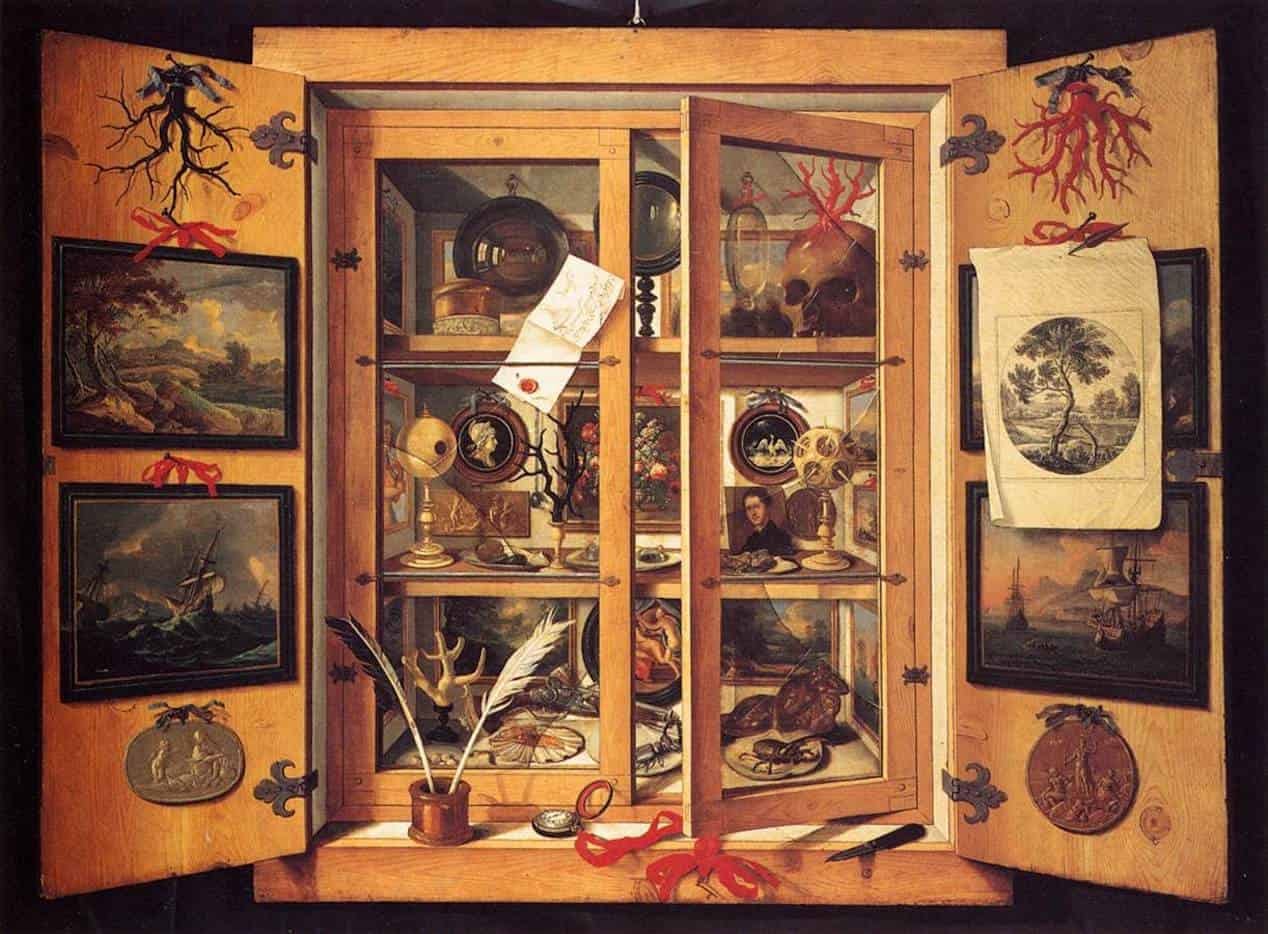

Cabinets of curiosity

Then, in mid-sixteenth-century Europe, we see the rise of the “cabinet of curiosities” — the precursors to modern museums.

Also known as wunderkammer or “rooms of wonder,” these cabinets marked the beginning of collecting as a hobby. They often contained a mix of naturalia (products of nature, such as shells), arteficialia (products of man, such as intricate jewelry, carvings, and ancient weaponry), and scientifica (scientific instruments, such as sundials and globes), and were common among scholars and royalty figures. These collections were early experiments in how to display your identity through stuff.

Democratizing the hobby

Collecting as a hobby really took off in the nineteenth century, right alongside the boom in manufactured goods. Suddenly, there was a lot more stuff around, and it was a lot easier for regular people to get their hands on it. It was around this time that stamp collecting took off, soon joined by coins, seashells, and books. Collecting picked up even more steam in the early 1900s in the US, as labor hours decreased and more people had time outside of work to devote to their curiosities.

Today, collecting belongs to everyone. Some collections are rare and valuable, but most are just intensely personal.

‘The past is not dead. In fact, it's not even past.’

Matchbooks from bars we’ve been to, band shirts from concerts we’ve attended, seashells from vacations, model airplanes, antique tools…

Why do people collect this stuff?

What’s behind our urge to keep and cherish certain objects?

Objects as markers of human history

The evolution of societies has always been defined by the objects they produce.

The Paleolithic period derives its name from the crude stone tools that were in use during its long millennia; Neolithic refers to the period in which stone was shaped to conform more and more precisely to the designs of its users. The Bronze and Iron ages define times and cultures in which things were first molded out of metal. Much later, the Industrial Revolution and the Atomic Age mark transitions in the processes of exploiting physical things for productive purposes.

From this perspective the evolution of humankind thus tends to be measured not by gains in intellect, morality, and wisdom; the benchmarks of progress have to do with our ability to fashion things of ever greater complexity in increasing numbers… Past memories, present experiences, and future dreams of each person are inextricably linked to the objects that comprise his or her environment.

—The Meaning of Things: Domestic Symbols and the Self, Eugene Halton and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi

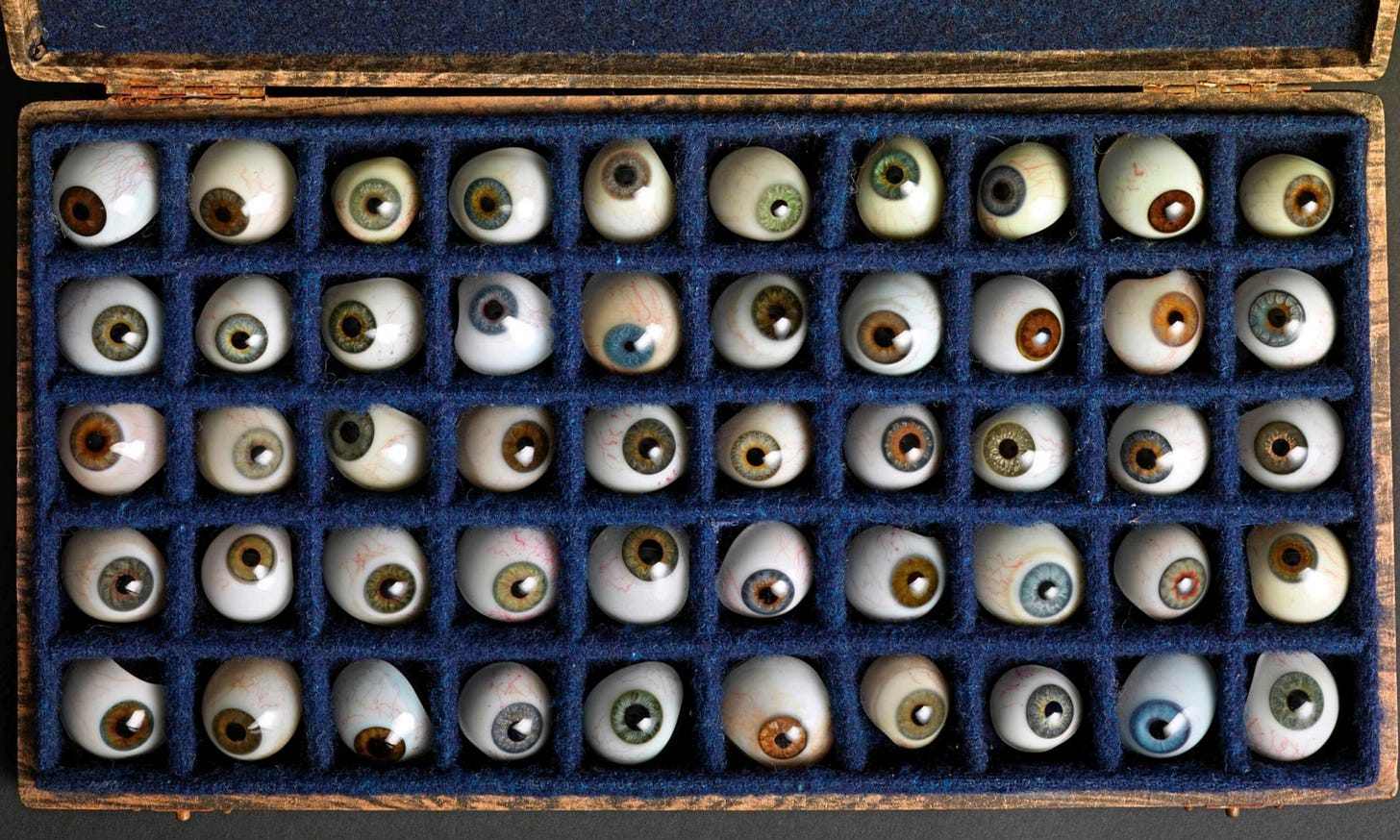

In other words, the things we keep and arrange become part of our environment, identity, and how we communicate with the world, both as individuals and as societies. Collecting is a deeply meaning-making activity: it weaves memories and longing into the everyday spaces we inhabit.

Objects connect us to the past. German existential philosopher Martin Heidegger argued that they are not just things, but heritage:

According to Heidegger, human agents are ‘thrown’ out of a past, into the present, as they project a future. In a sense, the human agent is ‘in’ all three dimensions of time at once.” In Heidegger’s terms, it is impossible for any of us to invent our life from scratch. Past objects have meaning for us today only because the past surrounds us as our heritage.

In a nutshell: Even the most mundane object (an old concert ticket, a pencil eraser) matters if it tells a story or sparks a memory.

Collections as reflections of identity

According to artist Louise Nevelson, “artists are born collectors.”

One of my enduring obsessions is learning about artists through the objects they collect. In my research, I’ve learned that I’m not alone in this.

In Lit Hub, Mary Kate Frank writes about the allure of Joan Didion’s objects through her experience traveling to Hudson, New York, to attend the auction of the late writer’s personal items.

“I believe there is power in the things our favorite writers keep close, the objects they run their fingers over: loose buttons in a box (Lot 169), seashells on a mantle.”

In a Harper’s Bazaar article titled “I Love Joan Didion’s Stuff,” Rachel Tashjian goes even further to assign meaning to Didion’s items:

“Things are treasures. [Didion’s] collection of seashells is a little aching; you can imagine her strolling some nearly empty beach, gathering them over the years. Each shell is the memory of some walk taken with a long-ago friend, of ideas first thought up and pains shared. It isn’t merely that seeing Didion’s stuff turns you romantic; the pieces are evocative. She pours meaning into her possessions, but seeing her possessions all laid out for us suggests there was something within these objects that she was waking up or unleashing with her tasteful mind.”

Elsner and Cardinal define three themes of collecting in their book, The Culture of Collecting: desire and nostalgia (missing things or wanting to recapture moments), saving and loss (holding onto what’s in danger of disappearing), and the urge to erect a permanent and complete system against the destructiveness of time (the desire to build something that says “I was here and this mattered.”).

Viewed through this lens, what do the collections of beloved artists and writers tell us about the individuals behind the objects?

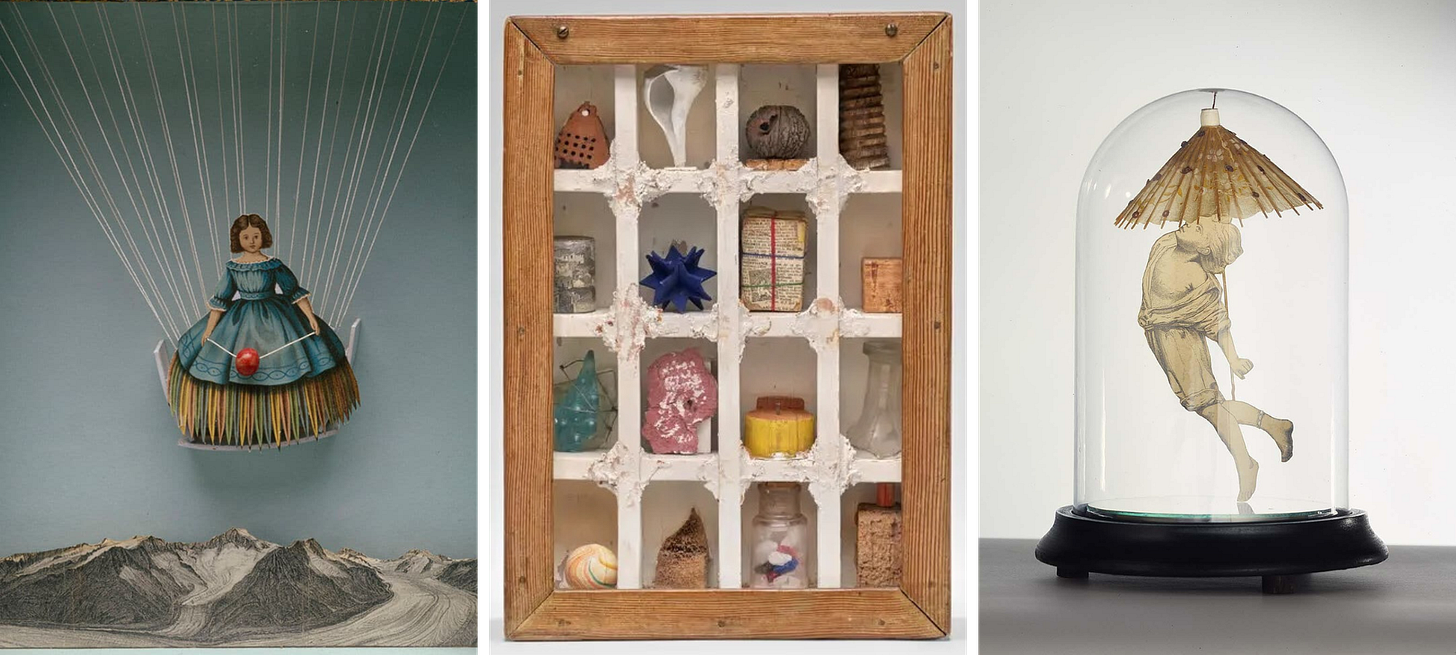

Desire and nostalgia: Joseph Cornell

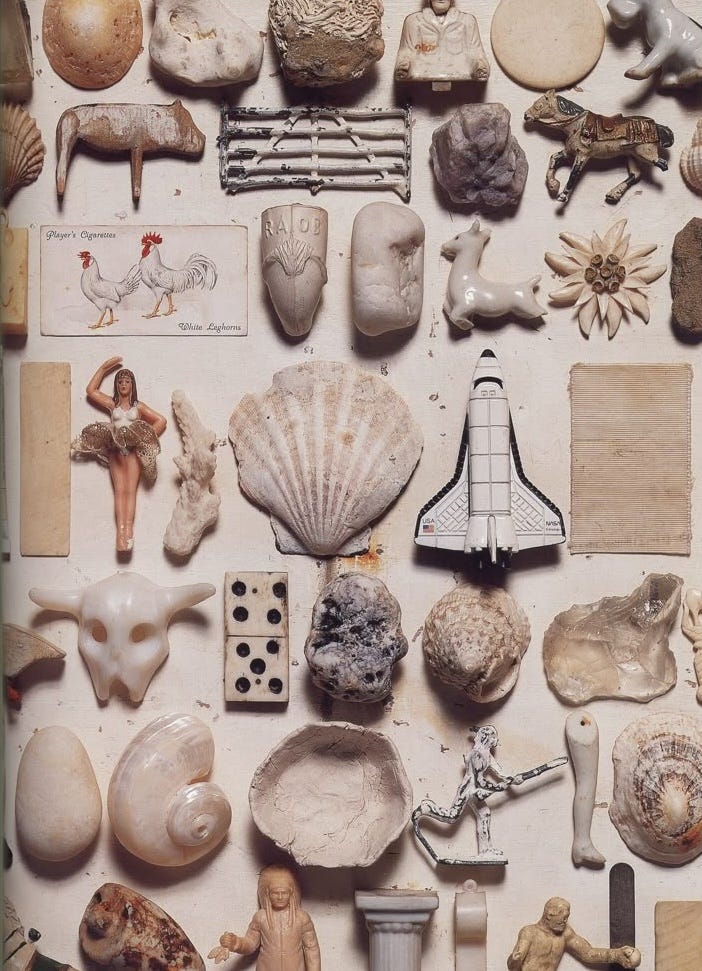

Before Joseph Cornell was an artist, he was a collector. He spent much of his time visiting New York City shops in search of items that sparked an emotional connection. A pioneer of assemblage art, Cornell crafted curious worlds in his famous boxes of arranged found objects—marbles, glass, snippets of ephemera, etc.—but his collecting was a personal compulsion first and an artistic resource second.

He was a meticulous cataloguer, housing his finds in shoeboxes and files, and described his storage as a “laboratory” for ongoing exploration and inspiration. While many collected items made their way into his collages and shadow boxes, his process began with collecting for its own sake.

Though he lacked formal art training, Cornell’s work drew inspiration from Surrealist friends and peers such as Max Ernst and Marcel Duchamp, blending the avant-garde with a personal nostalgia reminiscent of Victorian craft.

His boxes celebrate his passion for collecting, often using the simplest forms and least expensive materials to create objects of intrigue and wonder.

“He was not collecting what are usually defined as collectibles — objects distinguished by their beauty or rarity or historical importance. Rather, he attached the highest value to objects of little or no intrinsic worth… a cursory glance at Cornell’s boxes could lead you to think that he was constructing reliquaries for coveted possessions, when in fact his talent lay in alchemising commonly discarded objects into a visually compelling state of being.”

For most of his life, he lived with his mother and brother in a narrow house in Queens. His collections, and the boxes he assembled, represented objects and worlds more widely traveled than he ever was himself.

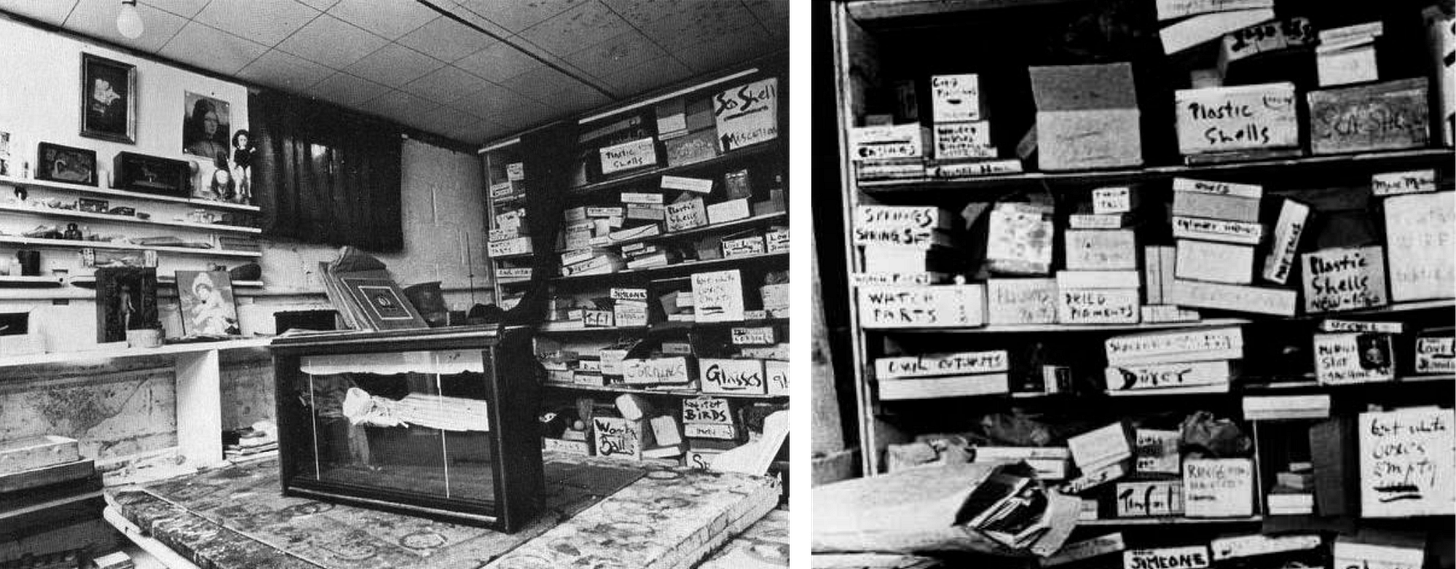

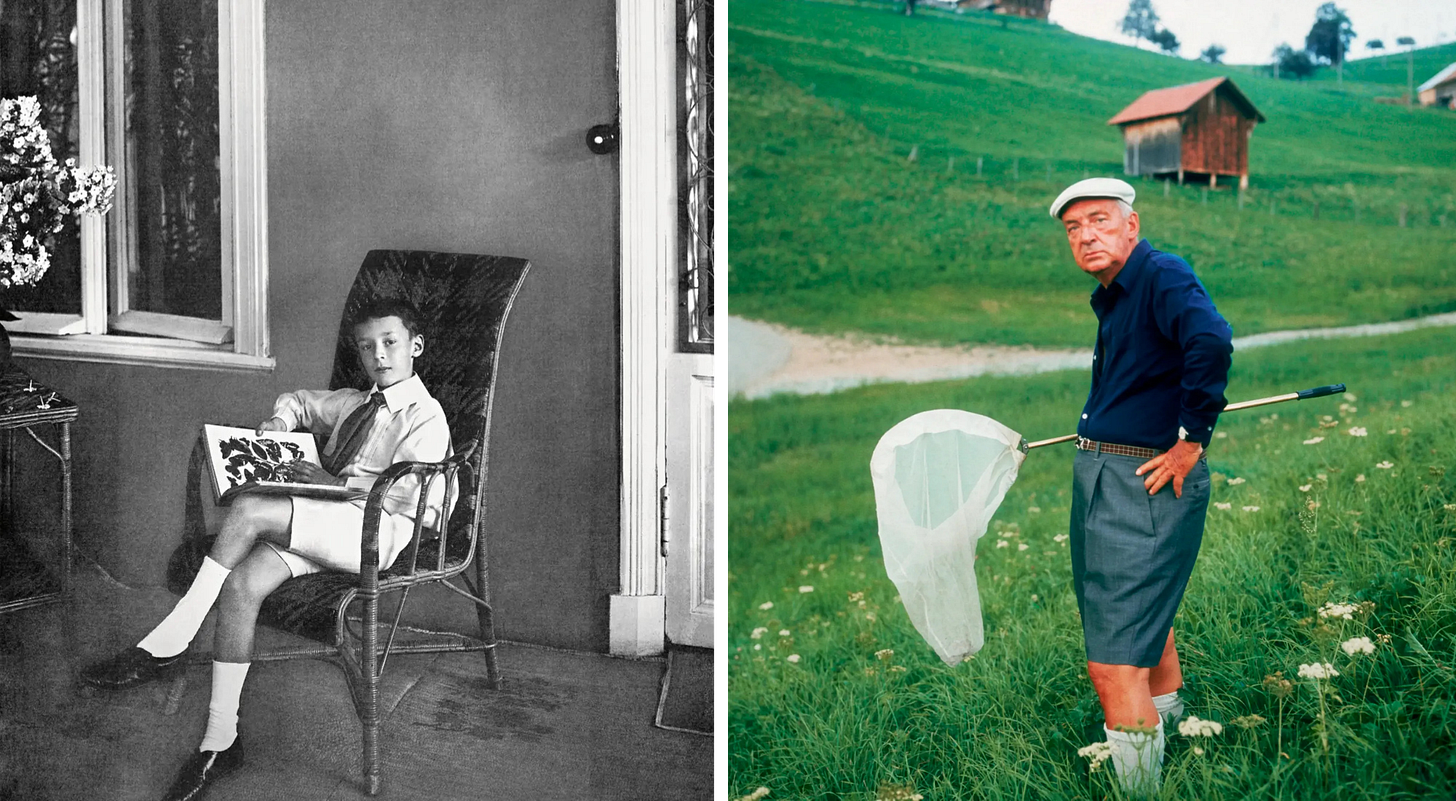

Saving and loss: Peter Blake

In a 2022 interview, artist Peter Blake recounted the trauma of his childhood: “When the second world war started, I was seven and I was evacuated, first to Essex and then to my grandmother in Worcester. It really took away [those years] for me. It was blank time.” That vacancy, that feeling of lost time and forced separation, became the impetus for his collecting.

Since he was a teenager, he’s been collecting everything from elephant toys and Disney memorabilia to jigsaw bits and jewelry.

The influence of these collections is apparent throughout Blake’s artistic output. Many of his found objects eventually became the materials for his iconic collages. (He’s most well-known for creating the cover of the Beatles’ Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album with his wife, artist Jann Haworth, though he’s stated that his lasting notoriety for this creation depresses him. He has referred to it as an albatross!)

In another interview, discussing his 2024 exhibition, “Peter Blake: Sculpture and Other Matters,” the artist explains his decision to buy a fleet of model galleons, revealing his affection for overlooked and under-appreciated objects:

“They’re the epitome of bad taste, aren’t they? No-one else was bidding.”

With Blake, the work seems to always follow the collecting. In a 2011 interview about an earlier show, “A Museum for Myself,” he says:

“In the exhibition there’s a whole collection of shell boxes and things decorated with shells. That really started when I was asked to do residency at the National Gallery, which meant I was going in every day on the train. On the walk to the station I passed three or four charity shops, here I saw this rather pretty little box covered with shells and bought that, and the next day in another charity shop there was another one, and suddenly I was collecting them. And then you watch out for them — most charity shops even now have something like that, so then you’re looking for them…

My artwork is also inspired by my collections — this really is what this show is all about — because it equally presents my work and the collections, and a lot of the work.

If you’d like to learn more about Peter Blake’s studio and practice, I enjoyed this studio tour produced by Tate.

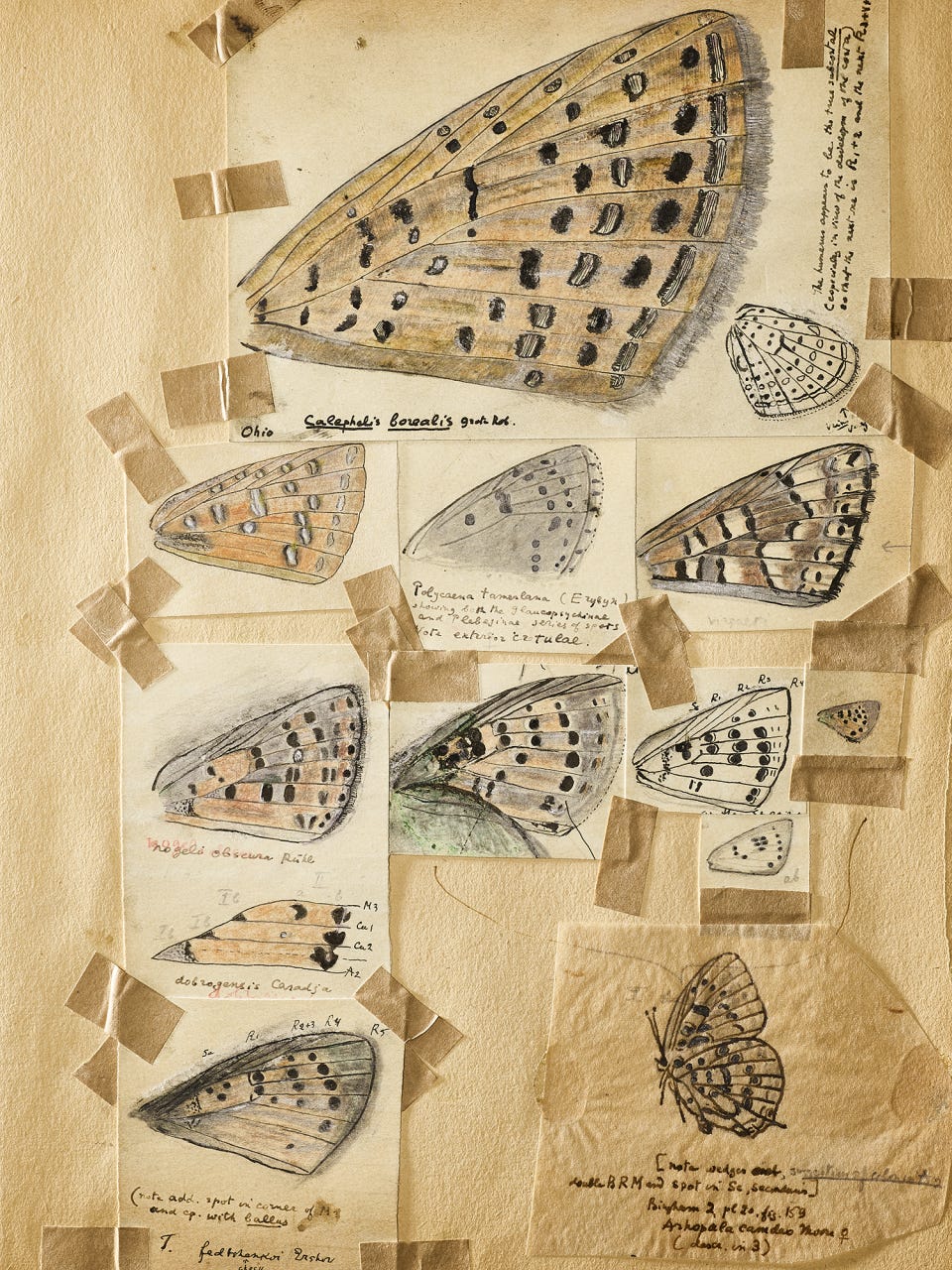

A system against the destructiveness of time: Vladimir Nabokov

“From the age of five, everything I felt... was dominated by a single passion. If my first glance of the morning was for the sun, my first thought was for the butterflies it would engender.”

–Vladimir Nabokov in “Butterflies” The New Yorker, June 12, 1948

Nabokov began collecting butterflies as a child in Russia, a passion encouraged by his mother, and this devotion would remain with him through exile, war, and fame. He once wrote, “I discovered in nature the nonutilitarian delights that I sought in art. Both were a form of magic, both were a game of intricate enchantment and deception.”

Nabakov’s Butterflies: A Timeline

1905 (age 6): Nabakov catches his first butterfly.

1907 (age 8): Nabakov brings a butterfly to his father who is in prison for political activities.

1917: Nabakov studies butterflies to ward off homesickness.

1940: Nabakov flees the Nazis to the United States, taking the job of Curator of Lepidoptera at Harvard University’s Museum of Comparative Zoology. During this time he spends up to 14 hours a day sorting and mounting butterflies and collecting butterflies around the country.

1945: Nabakov develops a theory of butterfly evolution that lepidopterists dismisses.

1958: Nabakov moves back to Europe, to Switzerland, partly for the butterflies in its alpine meadows.

1977: Nabakov has a bad fall on an alpine slope during a butterfly-catching expedition and sustains serious injuries. Later that same year, he dies in the hospital from bronchitis.

2011: Nabakov is vindicated when scientists confirm his theory of butterfly evolution using gene-sequencing technology.

Nabokov’s butterfly collection numbered over 4,000 specimens, representing more than 80% of Western Europe’s varieties, along with countless North American species gathered during his years in the United States. He donated hundreds of butterflies to Cornell University, and additional significant portions of his collection are held at Harvard University’s Museum of Comparative Zoology and the Nabokov Museum in St. Petersburg. These meticulously gathered specimens, some of which traveled with Nabokov across continents during war and exile, are a testament to his lifelong devotion to lepidoptery.

Fun fact: At least 570 mentions of butterflies have been counted in his literary work and over 20 species of butterfly have been named after his fictional characters.

For more on Nabakov’s butterflies, may I suggest this book on his butterfly art? I also thoroughly enjoyed Jenna Park’s post on what Nabokov’s butterflies can teach us about science and art. (Ironically, she also published an essay today on the collection of objects, which I have yet to read but am very much looking forward to diving into.)

If you’re in New York (through August 30)

Yuji Agematsu’s extraordinary daily “zip” sculptures—three hundred and sixty-six of them displaying like a year’s worth of miniature time capsules—are on view right now at Judd Foundation (SoHo) and 229 Lenox Avenue (Harlem), Fridays and Saturdays, 1–5pm. It’s a rare chance to experience the power of collecting in person.

This essay was a beefy one, and there are many artist-collectors who were not mentioned. If the topic intrigues enough of you, I may turn it into a short series spotlighting artist-collectors.

In the meantime, I’d love to know: what do you collect?

Elsie, I loved this piece so much. I lost my home in the Palisades wildfire last January, and I can't tell you how many people have said to me, "Oh well, it's just stuff." This beautiful piece gave me the words for an interior experience I haven't been able to adequately explain -- it was not just stuff -- it was my identity, my heritage, the collection of things that held me and my family and my memories. Thank you so much for writing this.

Elsie, we are on the same wavelength. I have been pondering my own collections (there are many!) and the story they are building. I find collecting and the motives behind it quite fascinating. Thanks for inviting us into a bit of your story (Piojito), and the collections of so many interesting artists.